GHP Recommends: Thanksgiving Reads

The Bonesetter’s Daughter by Amy Tan. If you have ever read an Amy Tan book, you understand how talented she is and how touching her themes are. The Bonesetter’s Daughter is no different. This novel is about Ruth, a successful first-generation Asian American living in San Fransisco and dealing with the decline of her mother’s mind to Alzheimer’s. But the story is about so much more than that. It’s about acceptance and understanding–the acceptance of ourselves and the understanding of where we come from. It is about forgiveness and empathy. It’s a story about love and healing. It is about culture and embracing the differences that make us who we are. This quote from the book always sticks with me: “You can have pride in what you do each day, but not arrogance in what you were born with.” I love this book–and Tan’s other books as well–and highly recommend! It’s a great Thanksgiving read; it has family, the melding of cultures, and thankfulness in its purest form.

Sister of my Heart by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni

In Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Sister of my Heart, Sudha and Anju are cousins growing up in the upper caste of Calcutta. The two are inseparable, constantly at each other’s side, until Sudha learns the truth about their family, making her feel distanced from her beloved cousin. The two girls drift apart, and then are firmly separated by their arranged marriages. Sudha remains in India while Anju moves to America with her husband. As each struggles on either side of the globe, they turn to each other for help and support, rekindling their friendship and relying on each other as they navigate their separate but intertwined lives. This book is a must read for insight into Indian society and the institution of arranged marriage.

City of Thieves by David Benioff. During the Nazi siege of Leningrad, a teen named Lev Beniov is arrested for looting and is tossed into a cell with a deserter named Kolya. Just hours away from the firing squad, they are spared at the last minute by a powerful Soviet Colonel who has a special job for them. His daughter is about to be married, and he wants them to find a dozen eggs for her wedding cake. This is a near-Herculean task in a city that is choked off from all supplies and suffering under the boot of the ruthless Nazi invaders. What follows is a true odyssey as the two set out to do the impossible in darkest depths of the lawless and war-torn Leningrad. I found this to be an entertaining adventure as well as a fascinating portrayal of the Soviet experience during the Second World War. Highly recommended!

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie. Junior has attended forty two funerals in his life. He’s fourteen years old. Growing up on a Spokane Indian Reservation, The Absolutely True Diary follows Junior as he seeks to figure himself out and his place in the world. Determined to take control of his own future, Junior leaves his Reservation school (where his textbook is the exact same textbook his mother studied from) to attend an all-white high school, where the only other Indian is the school mascot. A budding cartoonist, the author illustrated the book with brutally cutting comics that add a whole new layer to an already complex and poignant story. It came highly recommended, and it lived up to my expectations. I laughed and cried a lot. Sometimes at the same time. This book hurts, but in a way that leaves you feeling like it was worth the pain.

Stone and Silt by Harvey Chute. Life in 1800s British Columbia isn’t easy for 16-year-old Nikaia, who is bullied and called a “half-breed” for having a Native mother. Things are further complicated when she stumbles upon a stolen cache of gold. When the police find a dead man nearby, her father becomes a suspect. Nikaia races to find answers and save her family. Meanwhile, she also explores her blossoming feelings for Yee Sim, the quiet Chinese boy whose parents run the local store. A beautifully written YA historical mystery, Stone and Silt combines the thrill of mystery with thoughtful depictions of Native culture and life in the 1800s.

Tracks by Louise Erdrich. Tracks is the third in a trilogy of novels, but it is earliest chronologically, so I recommend new readers start here and, if you like it as much as I did, move on into the saga.

Tracks explores the interrelated lives of four Anishinaabe families living on an Indian reservation in North Dakota, told through the alternating first-person narratives of Nanapush, a tribal elder, and Pauline, a young half-blood girl. The story centers around events between 1912 and 1924, while the tribe was still struggling to keep their remaining lands. Over the ten-year span, tribal land was growing more and more scarce, mirrored by the trust of the people. People were pushed to the edge, friendships were forged only to be lost, and families were torn apart as they struggled to survive–to find their place in the ever changing world.

Nanapush is probably my favorite character; I associate him strongly with the coyote from the old lore. His trickster qualities help him throughout, and he claims, in his own defense, that “it is the tricksters who survive to build a new world on the ashes of the old.” In the tension between the Anishinaabe and the whites, he shows remarkable resilience, navigating both sides of every conflict, as any trickster would. He’s a prankster of sorts, but one could argue that his intentions are good; mostly, I saw him as the kindly, comedic, mischievous-but-harmless, and ultimately lovable sort. Pauline is something else, entirely; she acts mostly as an observer to the main events, but somehow, for me, always feels like an antagonist. As a teenage girl of mixed descent, she abandoned the traditional ways of her family, deciding to be more ‘white.’ She meets Fleur (Nanapush’s daughter) and is initially drawn to her power, but eventually falls into jealousy and obsession, furthering, if not creating, a lot of the conflicts that Fluer faces.The narration is unique in that, at times, the voices seem strangely unreliable. It may sound odd, but this is one of my favorite things about this book, as well as many of Erdrich’s other works. As we view the story through the eyes of each character, we are truly seeing them as they would, with themselves right and their opponent wrong, or their inability to see their own fault when such conflicts arise. Its a beautiful portrait of the human condition in that aspect.

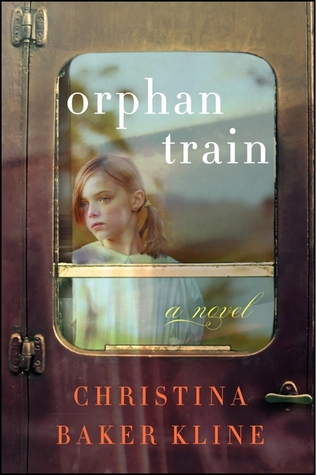

Orphan Train by Christina Baker Klein. This book features two main characters: an orphan of Native American descent in the present, and an orphan of Irish descent during the 1800s, when orphans were moved by the thousands from New York City to ‘adoptive’ families in the Midwest. Although Molly, the Native American character, focuses only briefly on her heritage and background, those few pages are powerful in their effect, and in highlighting the experience of many modern-day Native American children. Having lost her mother and father at an early age, she’s been moved from the squalid trailer in which they lived to a number of foster homes, none of which fit. We see a picture of a girl who grew up in poverty, on a reservation and amidst people that she both needed and didn’t fully understand. Then, thrust into the Western world, and torn from her heritage, she finds herself in home after home with people who can’t sympathize with her background, and therefore mistreat her. When eighteen-year-old Molly meets ninety-year-old Vivian, they begin to share their stories of grief and alienation at the hands of ‘the system,’ and once again find a sense of family and belonging. This is a lovely story that left me sobbing, and I’d recommend it to anyone with a love of history and coming-of-age novels.

Leave a Reply